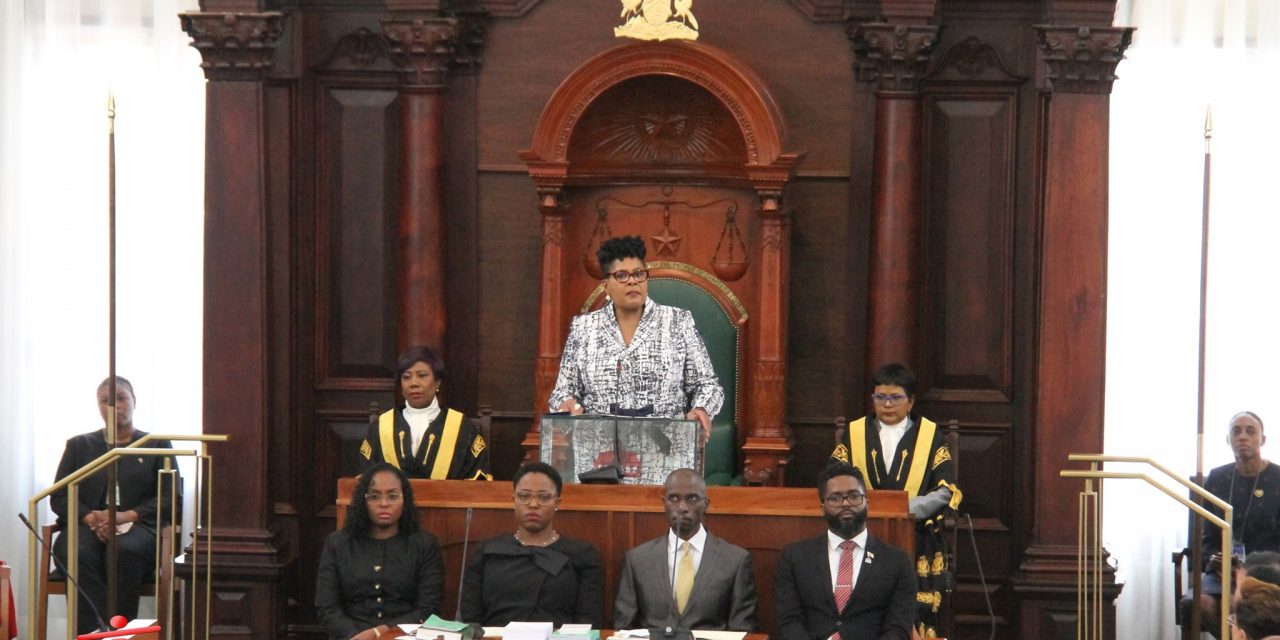

Madam President of the Senate, Madam Speaker of the House, Honourable Members of Parliament. Our Constitution provides that ‘There shall be a Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago which shall consist of the President, the Senate and the House of Representatives’, and further, that ‘Parliament may make laws for the peace, order and good governance of Trinidad and Tobago.’ I am pleased to see that the interpreters of these laws are among our number this morning.

As President, my parliamentary role, though essential, is perhaps the least significant. My power and authority is, by law and convention, limited ultimately to acting on the advice of Cabinet once necessary legal requirements have been satisfied. Another indication of how circumscribed my role is, is that I am here only by invitation issued by the Speaker of the House. I thank her for allowing me the honour of addressing you at the Re-Opening of the Red House and the Return of the Parliament to the Red House—a long awaited return as this is the first time that Parliament is sitting here since 2011. I was tempted to speak this morning about National Pride, but there will be sufficient other occasions for that.

In determining the subject of today’s address, I thought it a good idea to look at addresses delivered by my predecessors in office on similar occasions. I also reviewed addresses by my counterparts in other jurisdictions with a similar colonial heritage where the Head of State is not the Head of Government. By and large, in those countries the Head of State’s address to Parliament follows the practice employed by Her Majesty the Queen who uses the occasion to outline Government’s legislative agenda for the parliamentary year.

Our Republican model has not followed suit, at least not in the last 4 Presidents, and themes selected by our Heads of State have been as different as were the Presidents themselves. I discerned no common thread and therefore concluded, that subject only to propriety and relevance, I am afforded license to speak as I see fit.

This morning I assume the role of emissary bringing to Parliament a message from the citizens of Trinidad and Tobago who have entrusted to us the solemn responsibility to make such laws that would enable them to live secure, productive, gratifying and peaceful lives. I receive correspondence from members of the public on a daily basis, complaining bitterly, in essence, that existing laws do not address their serious concerns and that some laws appear to benefit narrow sectarian interests rather than the interests of all. I suspect that citizens write me because they harbour the mistaken belief that I have the jurisdiction to take action directly and/or to issue orders to the powers-that-be. We assembled know better.

And so I deliver their message—a message which they feel that neither Government nor Opposition is hearing, or if hearing, ignoring. And the message is as simple as it is poignant, they are hurting. While Parliament and other leaders in the country are dabbling in semantics about whether we are a failed State or in a crime crisis, our citizens are being murdered at an alarming rate, they lack opportunities for employment or are losing their jobs, food prices are spiralling beyond the reach of many, and more and more of our children are falling into the “at risk” category. Citizens are entitled to look to you for and demand of you solutions to alleviate their pain. They want you to work together for their good. Even the most desperate understand the nature of politics and that some degree of toeing the party line, posturing, old talk and picong come with the territory, but at the end of the day fidelity to the people, our vulnerable women, our defenceless children, our angry young men, must be the primary and paramount concern of Parliamentarians.

I suspect that the grand and august ambience of parliamentary chambers, and this one is no exception, is meant to reflect the sacredness and solemn duty which all but a few of you actively sought. Citizens cannot be faulted if they expect their business to be handled with complementary dignity and decorum—and with a degree of urgency.

Allow me to digress briefly. The Independent bench, the 9 impartial representatives of the people, without political agenda, are essential and valuable members of Parliament. By their probing, testing and questioning of proposed legislation, they, devoid of partisan interests, bring to the table a necessary even-handed approach. I take this opportunity to thank them for their service to country. The important and increasing demands on them dictate that, if they are to function effectively, they be appropriately accommodated and equipped to perform their roles.

In 22 months in office, I have assented to forty-six Acts of Parliament, issued twenty-three Proclamations, but the man in the street, the executive in the office and the public servant in the ministry would be hard pressed to find, far less measure, any improvement in their day-to-day circumstances. Of course, not every Act can yield immediate or short-term results, but there needs be legislation that addresses and ameliorates promptly critical and pressing issues confronting our population.

The job of a Parliamentarian can be a thankless one; it is not for the faint-hearted or thin-skinned. Even when legislation has been brought to the floor and thoroughly debated, citizens may still question its relevance, effect and impact on their daily lives and welfare. Legislation then is ineffective and unfruitful if it does not redound to the benefit of the citizens.

I have repeated ad nauseum that citizens have an onus on them, which they can neither deny nor shirk, to contribute to their overall wellbeing. They have their role to play in making this country one of which they can be proud, but they are dependent on those of us assembled here to lead the way, to provide avenues and opportunities for improvement and to model desirable conduct.

Parliament sets the tone for the average man in the street. If you are seen to treat each other with respect, courtesy and good humour, there can be a trickle-down effect and eventual cascade; but when acrimony, contempt and divisiveness is the example you set, you cannot be surprised when those attitudes and behaviours are replicated on the nation’s roads, in our schools and homes and on social media.

Awesome power resides in these Chambers and citizens are entitled to expect us to work together to give them, not only their constitutional due, but also the blueprint for national conduct. Law and order, truth and justice, morality and decency—these are the values which should be associated with our Parliament.

A well-established columnist in an article shortly after my inauguration commented that I reminded him of a stern long-time, creole auntie-tantie. I accept that as a badge of honour since, in my experience, auntie-tanties are usually proponents of sober thinking, discipline, good behaviour and deep reflection. They often tell us what we already know and use opportune moments such as these to give timely reminders, in case we have forgot.

I hope and pray that as I address this Parliament, holding myself out as a voice for citizens, it is not a voice crying in the wilderness.